How has the Amazon forest changed in 2022 and 2023? Which areas were affected and which are the main drivers of forest disturbance? The report Deforestation and forest degradation in the Amazon - Update for year 2022 and link to soy trade investigated the change dynamics in Earth’s largest rain forest region. The Amazon forest has a crucial role as climate stabiliser at local, regional and global scale, as a carbon sink and as container of an immense floral and faunal biodiversity.

According to JRC data, the Amazon has lost more than 35,000 km2 of intact humid forest in 2022, due to deforestation and forest degradation, which constitutes an increase of almost 15% compared to 2021. The trend for 2023 is slowing down, at least for Brazil, as deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has decreased by almost 50% in the first 10 months of the year.

However, the eight countries that share the Amazon region don’t show uniform trends of forest cover change; while e.g. Venezuela showed a sharp decline over the past two years, Bolivia’s rain forests are under great pressure since a few years, forest disturbances (i.e. deforestation and forest degradation) have risen almost 40% in 2022.

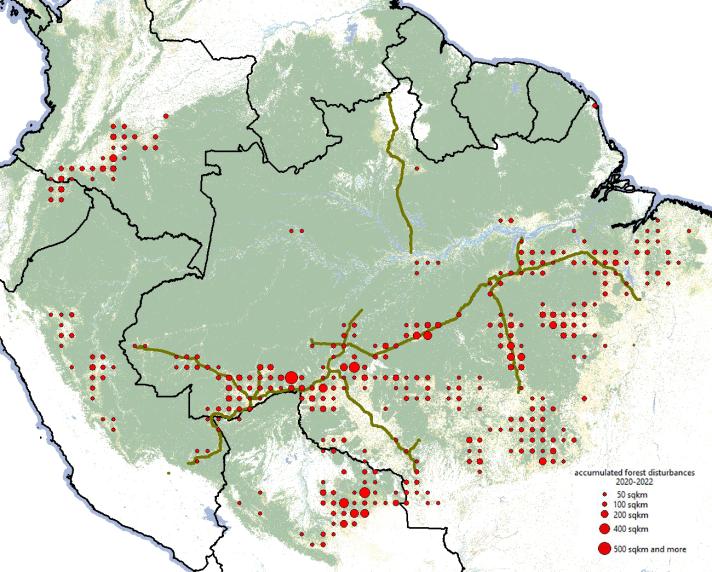

Recent Amazon forest disturbances, i.e. deforestation and forest degradation areas either happen at the edges of the Amazon forest like e.g. in Colombia, Peru and Ecuador. Specifically in Brazil, new deforestation frontiers are created along the mayor consolidated highways cutting through the Amazon forest. In the Southern and Eastern Amazon multiple access routes to the forest exist, thus the forest disturbance areas are more widespread rather than being concentrated along single major roads.

While Brazil has lost the largest area of intact humid Amazon forest in 2022, Bolivia and Ecuador have had more forest disturbances in relative terms, with a 2.5% and 1.8% intact forest loss, respectively (Brazil is third with 0.8%).

Deforestation and soy production in the Brazilian Amazon

Soy cultivation has expanded to the Southern Brazilian Amazon in the past two decades and has been exposed as one of the mayor drivers of deforestation in the region. Soy fields are often established after ‘taking over’ previously deforested areas that had been used as cattle pasture first.

Our report shows that the time offset between the use of a pasture to soy varies according to soy field size and geographic region and ranges from a local average of five to 20 years. Growing global demand, favourable prices as well as (planned or existing) improvements of soy transport infrastructure to the coastal or river ports for export give incentives to enlarge the soy production areas in the Amazon.

The Brazilian soy expansion has been fuelled by the soaring global demand for the commodity over the years. The EU is the second largest importer of soy and embedded tropical deforestation after China, outsourcing the environmental impact of its food consumption. Tropical deforestation is estimated to account for one sixth of the carbon footprint of a European citizen’s diet.

On 31 May 2023, the EU adopted a new Regulation on “deforestation-free products” (Regulation (EU) 2023/1115), which covers seven commodities (soy, cattle, palm oil, cocoa, coffee, rubber and wood) and their derived products, such as leather, chocolate, tyres, or furniture. Under the regulation, the actors in the supply chain (e.g., operators or traders) must demonstrate that the products placed on the European market do not originate from recently (after 2020) deforested land.

This is an important attempt to reconcile trade and sustainable modes of production and achieve more sustainable soy supply chains. In this context, it is essential to understand the dynamics of production and trade of commodities such as soy in relation to deforestation trends in the Amazon ecosystem.

Deforestation, forest degradation and policies – the case of Brazil

In 2023, policy changes and better law enforcement led to a significant increase in fines, notifications, embargoes, and confiscations linked to illegal deforestation and selective logging. In the first 10 months of 2023, deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon decreased by nearly 50% compared to the same period in 2022, while forest degradation was 33% lower. The Amazon Fund, mainly financed by Norway and Germany, was unblocked, and can now be used – as planned – for sustainable development of the Brazilian Amazon region.

An important first step towards a better protection of the Amazon forest and the support of indigenous people at the beginning of 2023 was the emergency response to the humanitarian crisis of the Yanomami People in the far North of Brazil, mainly caused by illegal gold mining in their territory. The Yanomami had suffered from malnutrition, diseases, mercury contamination and violence.

However, further work on existing and deployment of new infrastructure projects, such as completing the asphalting the BR-319 highway Porto Velho – Manaus (facilitating road transport of commodities like soy, cattle and wood), and building the planned Ferrogrão railway (running from the soy fields of Mato Grosso to the ports on the Amazon River), could negatively affect Amazon environmental protection.

Road asphalting in the Amazon can facilitate the migration of actors and processes from Brazil’s notorious ‘arc of deforestation’ to most of what remains of intact Brazil’s Amazon forest, especially if law enforcement is not secured. The Ferrogrão railway could give incentives for further expansion of soy cultivation (potentially causing direct or delayed deforestation), due to more competitive grain transport prices at international level.

Plans for gas and oil extraction in the western Brazilian Amazon and at the estuary of the Amazon River, and for construction of a large number of hydropower dams in the Amazon region can bring economic incentives, but could have an irreversible negative impact on forests, the aquatic environment and indigenous people.

Continued collaboration with Brazilian researchers

The JRC has a long-standing research collaboration with the Brazilian Space Research Institute (INPE), under the umbrella of the Cooperation Arrangement between JRC and MCTI (Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation). In this context methods for remote sensing – based tropical forest cover change monitoring have been jointly developed.

This cooperation is foreseen to intensify with the new Amazonia+ project, launched by the Commission’s Directorate-General for International Partnerships (INTPA). In addition, within the same project, two Brazilian researchers will be hosted at the JRC for one year to work, jointly with JRC colleagues, on the automatic mapping of forest degradation drivers in the Brazilian Amazon.

Related Links

Deforestation and forest degradation in the Amazon - Update for year 2022 and link to soy trade

Deforestation and forest degradation in the Amazon - Updated status and trends for the year 2021

Deforestation and forest degradation in the Amazon - Status and trends up to year 2020

EU observatory on deforestation and forest degradation

Tracking long-term (1990-2022) deforestation and degradation in tropical moist forests

Long-term (1990–2019) monitoring of forest cover changes in the humid tropics

Details

- Publication date

- 28 February 2024

- Author

- Joint Research Centre

- JRC portfolios