One in every 10 adults (16-74 years) in several EU countries has used online platforms at least once to provide labour services.

While for the majority it remains only a sporadic source of secondary income, 2% of the adult population works more than 20 hours a week or earns at least half of their income via online labour platforms.

These figures come from a new survey by the Joint Research Centre. Responses from more than 32 000 people across 14 Member States help to outline the main characteristics of platform workers, learn about their working conditions and motivations, and describe the type of services provided through digital labour platforms.

The main findings and policy implications are summarised in a report Platform Workers in Europe.

Tibor Navracsics, Commissioner for Education, Culture, Youth and Sport, responsible for the Joint Research Centre, said: "Many of us have already used digital platforms as customers, perhaps without realising what a difference they make for workers.

This report provides a solid basis to understand how these platforms work and how they affect developments in the labour market so that we can improve EU policies to help people get jobs and to protect them when they use these fora to offer services.”

Who are digital platform workers?

Digital labour platforms are leading to new forms of employment and work organisation.

They match workers with clients and provide the infrastructure and the governance conditions for the exchange of work and related compensation.

In the report, digital labour platforms are grouped in three categories: online freelancing platforms (such as PeoplePerHour, Freelancer and Upwork), microwork platforms (such as Amazon Mechanical Turk and CrowdFlower), and platforms that mediate physical services (such as Uber and TaskRabbit).

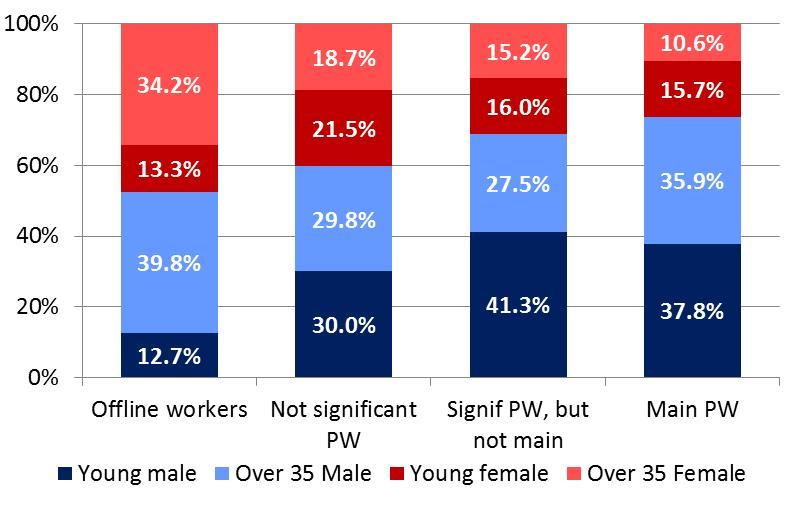

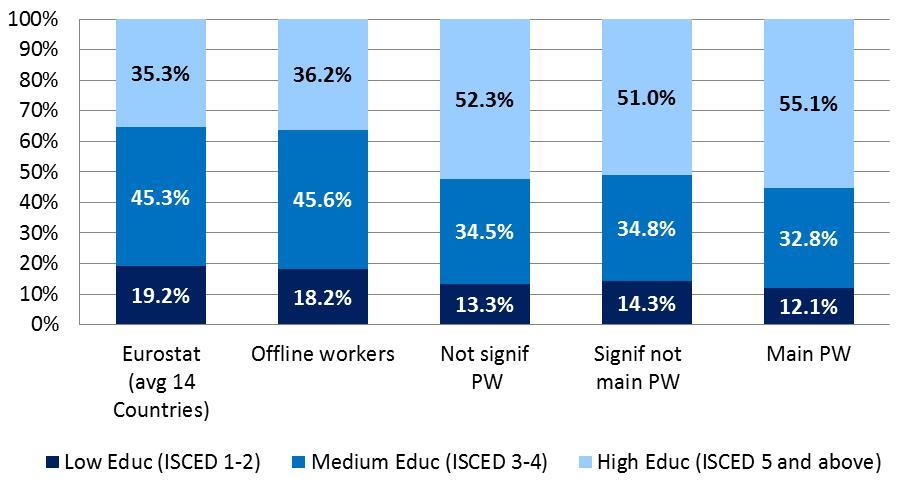

According to the new data, a typical European platform worker is a young male, with a higher education degree and fewer years of labour market experience than the average traditional, or off-line, worker in any age group.

There are fewer women among platform workers, and their ratio decreases as the intensity of platform work increases. Contrary to popular perceptions, a significant proportion of people for whom platform work is an important source of income have family responsibilities (including dependent children).

The data showed significant differences across the countries studied. Among the 14 EU countries in the study, the UK has the highest share of people working mainly through digital platforms (4.3%). Other countries with high relative values are the Netherlands (2.9%) and Germany (2.5%), whereas Finland (0.6%), Romania (0.8%) and Slovakia (0.9%) show very low values compared to the rest.

Platform workers: age and gender according to the intensity of their platform work

Source: Authors' elaborations using survey data. Data weighted using population weights. PW: Platform work. Significant PW: at least one quarter of the standard workweek of 40 hours or of the total income. Main PW: Workers who earn 50% or more of their income or work more than 20 hours a week via digital platforms.

What types of services are provided via digital labour platforms?

Labour services provided by digital platforms can be broadly divided into services provided digitally (such as micro tasks including content review and website feedback, or clerical and data entry like customer and transcription tasks) and services provided on-location (such as transport, delivery, housekeeping, etc.)

On average, half of the platform workers perform both digital and on-location services, and are active on two or more platforms.

The majority of platform workers have provided professional services (such as software development, writing or translation) which demand high skills.

Services that require medium skills are grouped as non-professional services (for example website review or sales and marketing support services) while on-location services (such as driving or childcare) in general demand low or no specific skills in the sense of qualifications.

One third of platform workers who perform only one type of service say that there is a mismatch between the lower-skilled tasks they perform and their level of education.

The most common labour service provided is online clerical and data entry.

Gender also influences the type of services provided. Software development and transport are the most male dominated services.

By contrast, translation and on-location services are mostly female dominated.

Platform workers: level of education

Source: Authors’ elaborations using survey data. Data weighted using population weights.PW: Platform work. Significant PW: at least one quarter of the standard workweek of 40 hours or of the total income. Main PW: Workers who earn 50% or more of their income or work more than 20 hours a week via digital platforms. ISCED – International standard classification of education.

Employment status and motivation of platform workers

Over three quarters of platform workers are either employees (68.1%) or self-employed (7.6%). Most of them have a regular job as a main activity and engage in platform work as a secondary source of income.

The survey results also suggest that a significant share of those platform workers who work more than 20 hours per week or earn more than half of their income via platforms consider their platform work as a form of dependent employment.

This contradicts the legal context, as providers of labour services via platforms are, in most cases, formally independent contractors rather than employees.

Flexibility and autonomy are frequently mentioned motivations for platform work, but results should be interpreted cautiously: a lack of alternatives is also often mentioned as an important motive.

Policy implications

In response to calls by the European Council and the European Parliament, the JRC, in collaboration with the European Commission's department for employment, social affairs and inclusion, has produced this survey and the subsequent report, as an initial attempt to provide quantitative evidence on digital platform work and reflect on its policy implications.

The emergence of digital platform work has important implications for employment, education and welfare policies. A critical obstacle to designing appropriate policy responses is the lack of reliable evidence.

The findings presented in this report suggest an emerging phenomenon of increasing importance but still modest size.

If platform work remains significant but small in the future, a two-pronged policy response is likely to suffice, focusing on fully grasping its job creation and innovation opportunities, and adjusting existing labour market institutions and welfare systems to the new reality and mitigating its potentially negative consequences for working careers and working conditions.

Examples of this are the proposal for a Directive on transparent and predictable working conditions (December 2017), and the proposal for a Council Recommendation on access to social protection for workers and the self-employed in the social fairness package (March 2018).

However, if platform work continues to grow in size and importance to become a more significant reality in our labour markets, or if some of the key features of platform work (such as the rating mechanisms) spread across other forms of employment, policy interventions may need to be further advanced.

Methodology

The survey, conducted by PPMI, is representative of all internet users between 16 and 74 years old in the selected countries.

The fieldwork was carried out in the second half of June 2017, with a final sample of almost 33 thousand (around 2,300 per country) across 14 EU Member States: Croatia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden and United Kingdom.

A second wave of the survey will be conducted in the second half of 2018 and it will include additionally Ireland and Czech Republic.

Related Content

JRC report: Platform workers in Europe

Commission press release: Commission adopts proposals for a European Labour Authority and for access to social protection (March 2018)

Commission press release: Commission proposes to improve transparency and predictability of working conditions (December 2017)

Details

- Publication date

- 27 June 2018