The JRC laboratory for alternatives to animal testing is 30 years old this year. A lot has been accomplished since 1991, but the mission is not over yet. We take a look at the milestones, achievements and the road ahead.

At the JRC’s Ispra site in Italy, the EU Reference Laboratory for alternatives to animal testing (EURL ECVAM) has been developing, validating and promoting scientific methods to replace animal tests for 30 years.

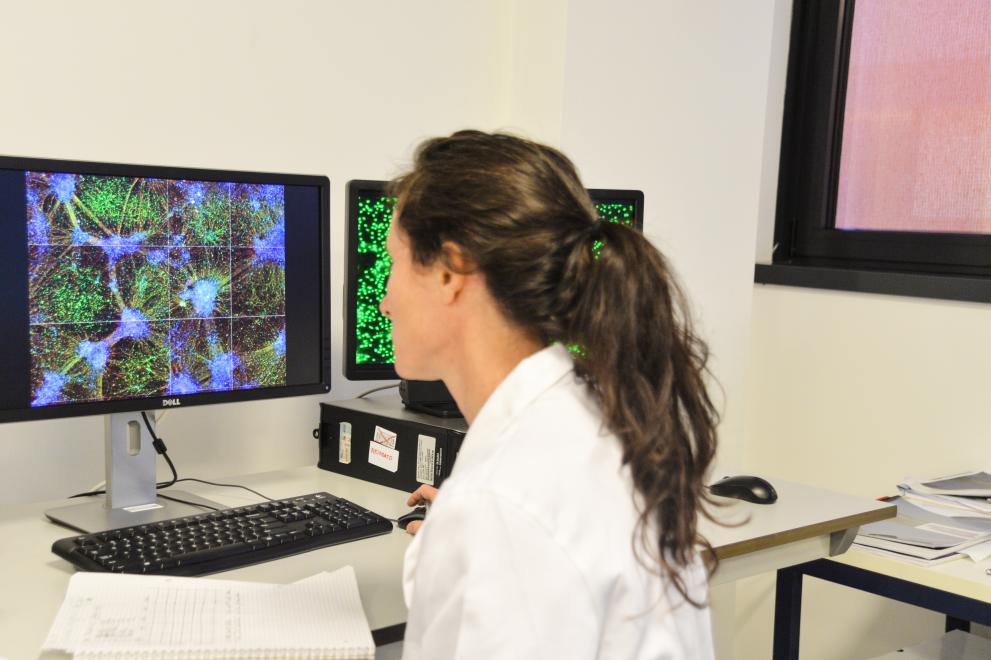

Researchers working at ECVAM are pushing scientific boundaries to identify new methods that will ultimately make animal testing redundant in the EU.

Non-animal approaches built around stem cells, engineered tissues, organ-on-chip, genomic techniques, computer modelling and artificial intelligence are already proving themselves as the tools of choice for research and testing.

JRC scientists believe modern alternative methods are more accurate in replicating human biology and function and thus better for understanding disease, testing new drugs or assessing the potentially harmful effects of everyday chemicals.

On the occasion of the 30-year anniversary and the publication of their latest status report, we talked with some of the team to understand where they’re coming from and what the future holds.

Alternative methods for toxicity testing

Valérie Zuang has been at the JRC since the early days of ECVAM and has worked extensively on in vitro methods to identify chemicals that can damage our skin and eyes. These methods use human tissues and cells cultured in the lab as an alternative to painful procedures carried out on rabbits.

“Thirty years ago, there were hardly any internationally recognised tests based on non-animal methods, so one of the first tasks of ECVAM was to prepare test guidelines and have them formally adopted in the EU and at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)”, Valérie remembers.

In 1991, there were only 7 OECD test guidelines based on in vitro methods, all for the purpose of identifying chemicals that cause DNA or chromosomal damage.

Today, there are 29 OECD test guidelines based on 49 alternative methods that cover many more areas, including skin corrosion and irritation, eye damage and so-called endocrine disruptors, which are chemicals that interfere with the natural hormone system. And three new test guidelines based on alternative methods addressing other toxicological effects are on the way, having recently been given the green light by international regulators.

These methods are used by chemical companies and regulatory agencies worldwide to protect human health and the environment while saving millions of animal lives.

“Since 1991, ECVAM has worked on over a hundred alternative methods at various stages of development, validation and acceptance. The very first one dates back to 1995 and was linked to skin corrosion testing”, Valérie adds.

Considerable contributions have also been made over the years to the validation and adoption of non-animal methods for the quality control of vaccines both within the EU and beyond.

The EU push

In the EU, legislation on the use of animals for scientific purposes has been in place since 1986.

In 2010, the EU Directive 2010/63 clearly set out the full replacement of animal methods as the ultimate policy goal.

“Apart from pushing down animal numbers and improving the culture of care, EU legislation has led to a lot more transparency. It enables us to compile detailed statistics on how animals are used in the EU and to understand where improvements can be made”, explains Pierre Deceuninck, data scientist.

In 1991, the very first statistics coming from the then 10 member states of the EU reported the use of 12 million animals. Fast forward to 2017 and an EU of 28 member countries, this number dropped to just over 9 million.

In 2013, the EU banned the sale of cosmetic products containing ingredients tested on animals.

Silvia Casati, a specialist in alternatives for skin sensitisation testing, remembers that before the cosmetics ban, there was hesitancy from the cosmetics industry to make the change.

“Now these companies are leading the development of new methods and proposing ways to optimally combine them within integrated testing and assessment strategies. There is healthy collaboration too within the sector which accelerates progress. No doubt the marketing ban at EU level had an important role to play in all this.”

Over the past two decades, the European Commission has funded over 200 projects related to alternative approaches with a total budget of over € 700 million.

According to Silvia, “The EU has been a pioneer in this area, and is showing global leadership in pushing for the development and adoption of alternative methods.”

It is about protecting humans too

The scientists believe that focusing only on ethical concerns conceals the important scientific benefits of switching to alternative methods.

“The ethical question of protecting animals is of course fundamental, and is at the heart of the debate about phasing out animal testing, but there is much more to this story”, comments Maurice Whelan, head of EURL ECVAM.

“Decades of biomedical research using animal models have produced no effective cures for many prevalent and debilitating diseases such as Alzheimer’s, the biggest cause of dementia worldwide.“

“And among the major causes for the failure of drugs to make it to market are a lack of efficacy and poor safety profiles that were not picked up in animal studies.”

“When you count the huge cost of failure in drug development and the burden on our national health systems caused by absence of effective treatments for diseases such as Alzheimer’s, a picture starts to emerge, which is one of flawed scientific strategies.”

“One might then wonder whether it’s actually ethical to continue to fund such strategies.”

Contrary to common belief, the majority of animals are actually used for basic and applied research and not for safety testing of drugs or chemicals.

"That's why we also invest heavily in education and training activities, and in ensuring that the latest scientific knowledge on alternatives is shared across different communities", comments Elisabet Berggren, an expert in new approaches to safety assessment. "One highlight is our JRC Summer School on non-animal approaches in science, where we get the chance to inspire the next generation of scientists and decision-makers, and they get to inspire us too".

Pioneers in non-animal methods 30 years ago, and pioneers still today, the JRC scientists still have their sights fixed on the ultimate goal: full replacement of animal methods in Europe.

“We are not quite there yet, and a lot still needs to be done, not only in terms of scientific advances but also in terms of raising awareness and changing mind-sets, but it's certainly far less of a challenge today than it was 30 years ago”, Maurice concludes.

Related Content

European Union Reference Laboratory for alternatives to animal testing (EURL ECVAM)

Details

- Publication date

- 3 June 2021