Despite the key role science plays in the implementation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, disaster science represents only 0.22% of the world’s total scholarly output.

The data suggests that countries focus their research on disaster types with high domestic relevance. Asia appears to have a central position in the disaster science field.

Disaster science has also an overall degree of international collaboration of 20%, which is slightly higher than the global average in all fields of science of around 18% during the time period covered.

These are several of findings presented in a new study, A Global Outlook on Disaster Science, released on the 20th November 2017 by Elsevier together with the international experts, including JRC scientists, and which will be presented at Bosai Global Forum on the 26th November 2017.

Focus on scientific research outputs

The World Economic Forum identified major disasters as one of the top five global risks in 2017. The risk and impact of major disasters have been exacerbated by climate change, growth in population and urbanization, and environmental degradation. These risk multipliers combine with other underlying factors—poverty, poor governance, and a degraded infrastructure—which further increase the severity of disaster impact on communities and populations. Disasters can be particularly devastating in poorer areas that are not as able to respond, putting a significant strain on humanitarian efforts to meet the needs of affected populations.

With the report A Global Outlook on Disaster Science, international partners and experts, provide a quantitative analysis of disaster science research from 2012 to 2016. Based on Scopus data the study analyzes more than 27,000 disaster science papers published between 2012 and 2016. It provides an evidence-based overview of the field of disaster science and offers insights that can help inform policy and decision makers to improve resilience to disasters both locally and globally.

A panel of 10 internationally recognized disaster science experts from partner organizations were consulted to identify and define the corpus of scholarly data to include in analyses, including scientists from the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission.

Results are framed around measures of research activity (output, impact, and specialization) for disaster science, as well for each of the four stages of disaster risk management: prevention, preparedness, response, recovery; and the ten disaster types defined by the Global Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction adopted by 187 United Nations member states in 2015.

© United Nations Office For Disaster Risk Reduction

What the findings say?

Despite the key role science plays in the implementation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, disaster science represents only 0.22% of the world’s total scholarly output.

The data suggests that countries focus their research on disaster types with high domestic relevance.

Asia appears to have a central position in the disaster science field. This indication by "A Global Outlook on Disaster Science" goes along also with an earlier released JRC's report "Atlas of the Human Planet 2017", showing that exposure to natural hazards doubled in the last 40 years, both for built-up area and population. Earthquake is the hazard that accounts for the highest number of people potentially exposed worldwide. Flood, the most frequent natural disaster, potentially affects more people in Asia (76.9% of the global population exposed) and Africa (12.2%) than in other regions. Tropical cyclone winds threaten 89 countries in the world and the population exposed to cyclones increased from 1 billion in 1975 up to 1.6 billion in 2015. The country most at risk to tsunamis is Japan, whose population is 4 times more exposed than China, the second country on the ranking. Sea level surge affects the countries across the tropical region and China has one of the largest increase of population over the last four decades exposed to this hazard (plus 200 million people from 1990 to 2015).

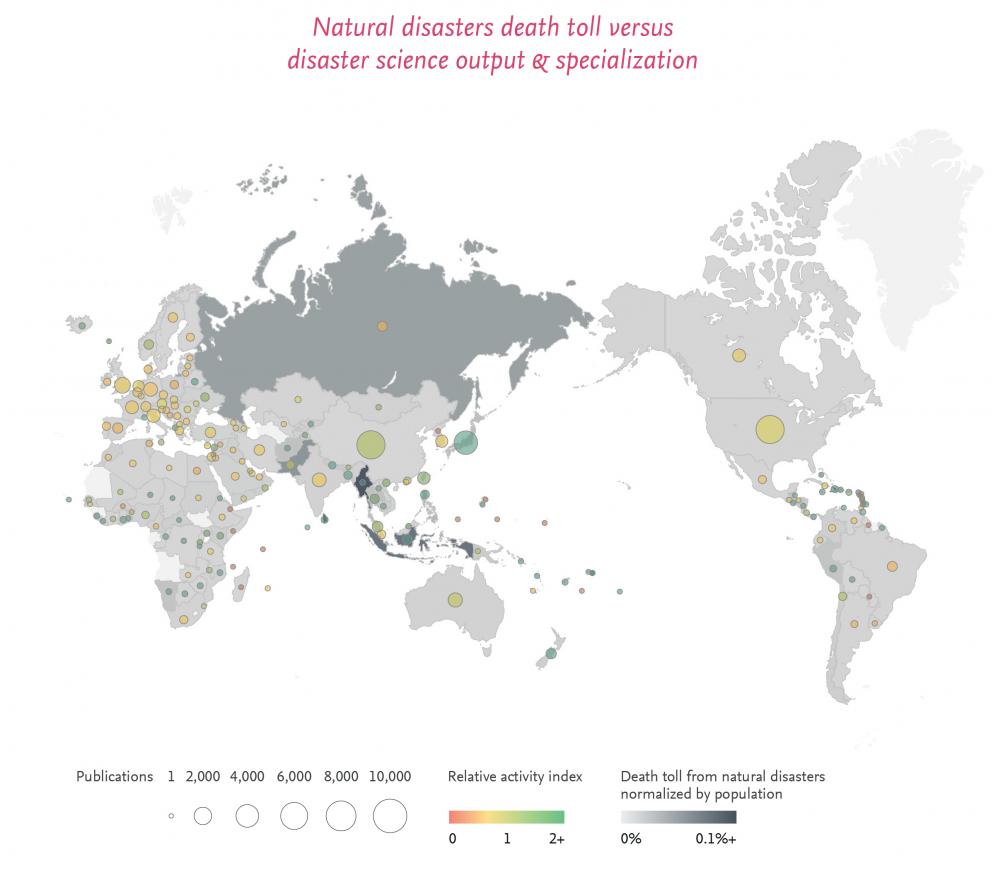

Worldwide however many emerging countries with high burdens of disaster-related human or economic loss publish few disaster science papers. For instance, Haiti has the highest human death toll relative to its population. Myanmar has the second highest human death toll relative to its population but only nine recent publications in the field. Sri Lanka has the third highest human death toll relative to its population and although its scholarly output is highly specialized in disaster science, its total recent output in the field consists only of 51 papers.

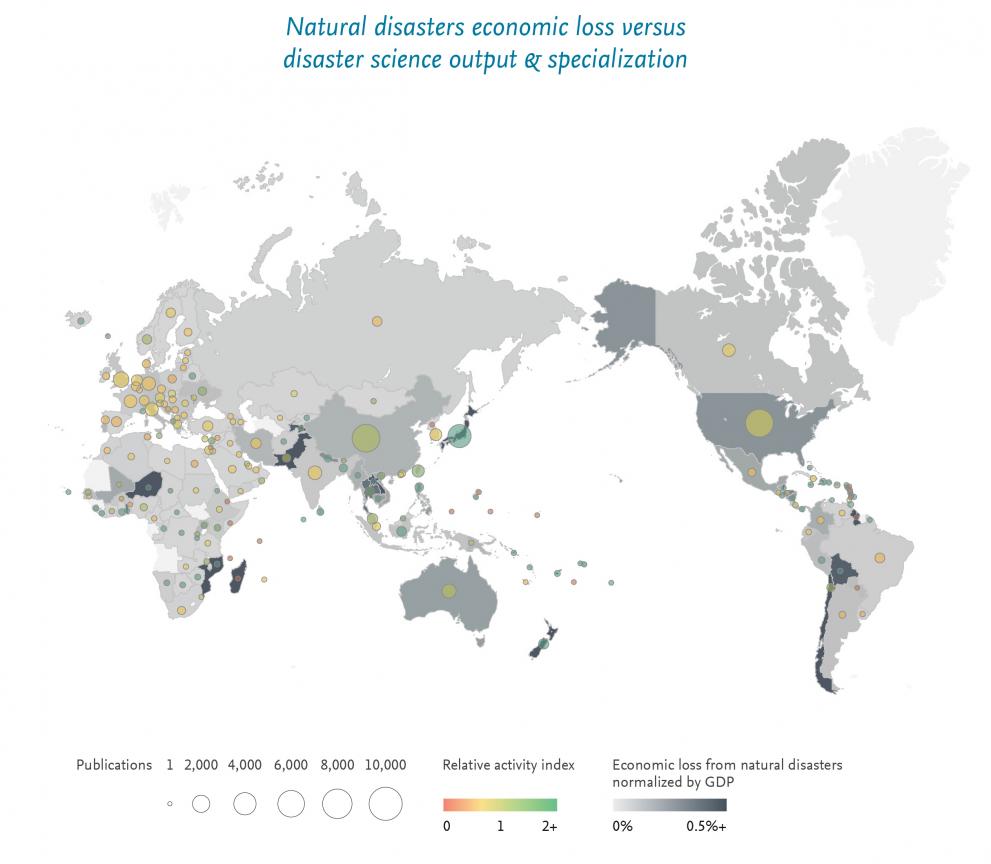

A "Global Outlook to Disaster Science" also finds that countries with the highest numbers of disaster science publications tend to suffer relatively low death tolls. These countries also tend to encounter high economic loss from natural disasters as these countries with the highest scholarly output in disaster science are intensive research nations that also lead in overall scholarly output.

It leads to hypothesis that one underlying variable in the uneven distribution of disaster science research may be overall GDP. Typically, a higher GDP permits higher investments in research, with more funding for research overall and in disaster science, which leads to greater scholarly output. It may also result in a resilient infrastructure that can help save lives and therefore reduces the human toll of natural disasters. A higher GDP may also allow for a more complex and expensive infrastructure, which in turn may lead to greater economic loss from natural disasters.

A report also draws attention that a high output or specialization in disaster science does not necessarily lead to high citation impact. For instance, although European countries tend to be less specialized in disaster science, they have a strong output and high citation impact in the field, exceeding that of their respective overall research performance.

Research is a key element addressing the full cycle of prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery in Disaster Risk Management. It is in cooperation with the research community that methodologies are formulated and tools are set up to address challenges. Therefore research communities that have less resources could benefit most from the international collaboration and networks that are particularly curtail in knowledge transfer, dissemination of good practices and scientific findings.

The report refers to numerous international initiatives in which the European Commission Joint Research Centre's scientists are actively taking part. It also outlines a number of possible subsequent in depth analyses, one of these being a connection between disaster science scholarity and policy making in more detail.

Related Content

European Commission Global Flood Partnership

European Commission Disaster Risk Management Knowledge Centre DRMKC

Science for Disaster Risk Management 2017: Knowing Better and Losing Less

Science for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2014

Words into Action Guidelines, UNISDR, 2017

Science is Used for Disaster Risk Reduction, UNISDR STAG, 2015.

Details

- Publication date

- 24 November 2017